Checks and balances…to some, it sounds like a personal finance concept. But to social studies teachers, it’s one of the most crucial ideas in American government that serve as an indicator of whether or not a student grasps other fundamental concepts like separation of powers and the three branches. In short, if your students don’t understand the meaning of checks and balances after a semester of civics, it’s time to remediate and fix the error.

Main Idea of Checks and Balances

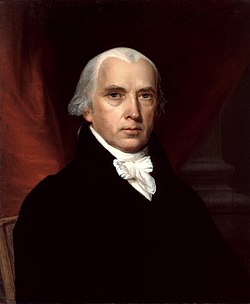

Checks and balances relies on the constitutional framework that provides for three branches of government, each with its own separate and distinct roles and powers. One Founding Father who detailed this idea while advocating for ratification of the U.S. Constitution was James Madison (see Federalist No. 47). Madison based his ideas about the separation of powers on the writings of French philosopher Montesquieu. In short, to avoid tyranny and absolute power in the hands of one branch or group of people, separate branches with the ability to “check” or cancel the actions of another branch were essential. In historical and modern terms, one quick example is detailed by the process of passing a bill and signing it into law: if a bill passes in Congress, it is up to the president to sign or veto–reject–the bill. It is not law until signed by the president. That’s checks and balances.

James Madison

Example 1: Legislative Checks the Executive

One role of the legislative branch involves the confirmation or rejection of presidential appointments. No, this does not mean that the Speaker of the House confirms that the president has a dentist appointment at 9 AM next Thursday. It means that when a recently elected president nominates someone to be his Cabinet secretary for the Department of Agriculture, the upper chamber in the legislative branch, the Senate, holds hearings to examine the background and qualifications of the nominee, and ultimately votes to confirm or reject the nominee to the position. That’s an example of checks and balances, and one in which the national legislature holds great power over the executive branch.

Example 2: Executive Checks the Legislative

One of the easiest to remember was detailed in the main idea earlier: the president vetoes a bill. In doing so, the president–the chief executive–has “checked” the power of Congress–the national legislature. Of course, as checks and balances go, if Congress can muster 2/3rds of its members to vote to overrule the president’s veto, the bill will become law, which is another way that the legislative branch checks the executive.

Example 3: Judicial Checks the Legislative & Executive

Another lesson for another time will be on the judicial power of judicial review, which was established in 1803 via the Supreme Court’s decision in Marbury v Madison. That said, judicial review is the power of the courts to overturn what are deemed unconstitutional laws. Clearly, the most landmark reversals are initiated by the U.S. Supreme Court, including Brown v Board in 1954, which overturned Plessy v Ferguson (1896, “separate but equal”). Put simply, when the judicial branch throws out an unconstitutional law, it’s a check on the legislative branch that wrote, debated and passed the bill, and the executive who signed it into law. This check illustrates the immense power of the Supreme Court and the judicial branch.

See Articles I, II and III

Of course there are many other examples of the three branches “checking” the powers of each other, and the primary source to those details is the U.S. Constitution, specifically in Articles I, II and III. However, I think the ones above are the easiest for middle school and high school students to grasp. What are some of your favorite examples of checks and balances? Leave your comments below.